When I started working for the HETE project as a young impressionable grad student, another scientist on the team gave me the rundown. There were "adults" and there were "kids." The "adults" on our project were a group of 6-7 principal investigators, senior scientists and full professors who were generally responsible for the broad scientific direction of the mission, press-releases, grant-writing, political arm-twisting, etc. Many of the adults maintained only a general understanding of the underlying working of the satellite and the software. The term "kids" wasn't limited to just mean grad and undergrad students, but also the group of non-professor-level Ph.D. scientists who actually ran the mission and knew what was going on day to day. When we went out for team dinners, the adults and the kids often sat at different tables and had entirely different types of conversations. Kinda like Thanksgiving with my family, in a way.

Now, having participated in two largish scientific collaborations I can say with certainty that the most crucial member of any team is the person (or sometimes, persons) you might describe as the "oldest kid." I think any good collaboration must have at least one of these. As an entering student, they are absolutely the person you go to when you want to know something and really understand the details of it. They tend to have an encyclopedic knowledge of who is an expert on 'x' issue, which students are working on 'y' calculation, and the best way to extract 'z' data product. They are traffic-directors extraordinaire. And most importantly, they communicate the nitty-gritty details upward to the adults and make sure they don't make dumb decisions for lack of understanding the facts on the ground.

They often don't publish a lot of papers or get a ton of recognition. Some may work an entire scientific career without truly joining the ranks of the "adults." But I'm convinced that without these oldest kids, the entire scientific enterprise would grind to a halt. I can certainly attest to how absolutely essential many of these people have been to me during my time in grad school. So here's to you, oldest-kid researchers! Huzzah!

Wednesday, June 28, 2006

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

Torture Awareness Month

Lest we think the ceremonial naming of months is merely a public relations tactic employed by for lobbyists from the Pork Council or the Canadian Dental Hygienists Association, this June is Torture Awareness Month. Of course, according to Wikipedia, June is also Samurai Awareness Month, so go figure.

Sadly, torture has become a terrible blot on our country, and the time has long since passed to make some noise. We've all heard the litany of abuse: First, Bush will not be abiding by the Geneva Conventions. Then (surprised?) the photos of abuse at Abu Ghraib. Thus far only a few lowly 'bad apples' are implicated, but as Sy Hersh reported in the New Yorker, the abuse was possibly orchestrated and approved by military intelligence in a desperate attempt to gather information on the insurgency. Guantanamo Bay and the mysterious 'black sites' in Europe and Asia, have become a land beyond law, where hundreds of people have been held incommunicado and largely without access to the courts. Now there have been 3 suicides. It has become so embarassing, that Congress even passed a law prohibiting the use of torture; Bush signed it, but then delivered a signing statement claiming he will obey the law only when it suits him. This is bad.

The pro-torture apologists always tend to come up with one of two responses: (1) the bad guys do worse things, or (2) the inevitable 'ticking time bomb' scenario.

The first argument, while emotionally appealing in light of some of the horrible things that go on in the world, is just morally dumb. That sort of argument didn't cut any ice in kindergarten and sinking down to the lowest level of humanity in our national policy is no way to run a country now that we're grown-ups (well, some of us anyway). It is, at it's core, a scare tactic. The strongest argument against torture is simply that it is evil and wrong. It was wrong when Saddam and Pinochet and others did it - it's still wrong now. The fact that we are a democracy is no fig leaf here. Indeed, it makes it all our responsibility.

The second argument shows how much Hollywood action movies have informed our political debate. We can just see Bruce Willis beating the crucial life-saving info out of some sweaty terrorist, defusing the bomb, rescuing his tough (yet imperiled) former wife and delivering comeuppance to the spineless bureaucrat. Go Bruce Go! The real-world, it turns out, isn't very much like the climax of an action movie. I know, I know, it's shocking to think that Hollywood has misled us on this matter, but it's true. The vast, vast majority of people in question are not Al Qaeda masterminds with secret information about imminent attacks. Most of the prisoners at Gitmo have been there for three years or more; even if they were once high-up in AQ (and almost all of them weren't) any intelligence they might have now is worse than useless. Some were 'bought' from Afghan warlords for $5000 a head. Some were picked up on 'hunch' of some CIA officer and later released without charges after it was apparent they were nobodies. Most of the prisoners at Abu Ghraib were taxi drivers in the wrong place or the brother-in-law of some wanted insurgent picked up in a general sweep.

It's never a good idea to base your official policy on a rare case. In the heat of the moment, it's too tempting to see every situation as life-or-death, when in hindsight it's really not. We would have to ask ourselves, how many innocent people do we want to torture in order to find that needle in the haystack that will hypothetically save American lives? 1000? 10,000? And remember, such a policy means 10,000 false leads to add to the top of the haystack (if you torture someone enough they will typically say anything to make it stop). It's also pretty easy to be pro-torture when you're white and/or American; you really don't have to worry that each time you board a plane, you might end up in a cell in Syria for ten months (as happened to Maher Arar).

And what have we lost in exchange for this hypothetical gain? We've lost the respect of our allies, confirmed fears that we are an unaccountable tyranny, spawned yet more insurgents and joined a tawdry fraternity of nations condemned by Amnesty and the Red Cross. To paraphrase Karl Rove, it will take the U.S. generations to live down the Abu Ghraib pictures and gain credibility in the Middle East. It's time we started making amends.

For ideas on how to make your voice heard: http://www.tortureawareness.org/

Join Amnesty International

Sign this petition: http://www.nrcat.org

Sadly, torture has become a terrible blot on our country, and the time has long since passed to make some noise. We've all heard the litany of abuse: First, Bush will not be abiding by the Geneva Conventions. Then (surprised?) the photos of abuse at Abu Ghraib. Thus far only a few lowly 'bad apples' are implicated, but as Sy Hersh reported in the New Yorker, the abuse was possibly orchestrated and approved by military intelligence in a desperate attempt to gather information on the insurgency. Guantanamo Bay and the mysterious 'black sites' in Europe and Asia, have become a land beyond law, where hundreds of people have been held incommunicado and largely without access to the courts. Now there have been 3 suicides. It has become so embarassing, that Congress even passed a law prohibiting the use of torture; Bush signed it, but then delivered a signing statement claiming he will obey the law only when it suits him. This is bad.

The pro-torture apologists always tend to come up with one of two responses: (1) the bad guys do worse things, or (2) the inevitable 'ticking time bomb' scenario.

The first argument, while emotionally appealing in light of some of the horrible things that go on in the world, is just morally dumb. That sort of argument didn't cut any ice in kindergarten and sinking down to the lowest level of humanity in our national policy is no way to run a country now that we're grown-ups (well, some of us anyway). It is, at it's core, a scare tactic. The strongest argument against torture is simply that it is evil and wrong. It was wrong when Saddam and Pinochet and others did it - it's still wrong now. The fact that we are a democracy is no fig leaf here. Indeed, it makes it all our responsibility.

The second argument shows how much Hollywood action movies have informed our political debate. We can just see Bruce Willis beating the crucial life-saving info out of some sweaty terrorist, defusing the bomb, rescuing his tough (yet imperiled) former wife and delivering comeuppance to the spineless bureaucrat. Go Bruce Go! The real-world, it turns out, isn't very much like the climax of an action movie. I know, I know, it's shocking to think that Hollywood has misled us on this matter, but it's true. The vast, vast majority of people in question are not Al Qaeda masterminds with secret information about imminent attacks. Most of the prisoners at Gitmo have been there for three years or more; even if they were once high-up in AQ (and almost all of them weren't) any intelligence they might have now is worse than useless. Some were 'bought' from Afghan warlords for $5000 a head. Some were picked up on 'hunch' of some CIA officer and later released without charges after it was apparent they were nobodies. Most of the prisoners at Abu Ghraib were taxi drivers in the wrong place or the brother-in-law of some wanted insurgent picked up in a general sweep.

It's never a good idea to base your official policy on a rare case. In the heat of the moment, it's too tempting to see every situation as life-or-death, when in hindsight it's really not. We would have to ask ourselves, how many innocent people do we want to torture in order to find that needle in the haystack that will hypothetically save American lives? 1000? 10,000? And remember, such a policy means 10,000 false leads to add to the top of the haystack (if you torture someone enough they will typically say anything to make it stop). It's also pretty easy to be pro-torture when you're white and/or American; you really don't have to worry that each time you board a plane, you might end up in a cell in Syria for ten months (as happened to Maher Arar).

And what have we lost in exchange for this hypothetical gain? We've lost the respect of our allies, confirmed fears that we are an unaccountable tyranny, spawned yet more insurgents and joined a tawdry fraternity of nations condemned by Amnesty and the Red Cross. To paraphrase Karl Rove, it will take the U.S. generations to live down the Abu Ghraib pictures and gain credibility in the Middle East. It's time we started making amends.

For ideas on how to make your voice heard: http://www.tortureawareness.org/

Join Amnesty International

Sign this petition: http://www.nrcat.org

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

Twisted Link 'o' the Week

I saw this at an animation festival years ago and very nearly actually died laughing. Click the red balloon. What a wonderful thing is YouTube that such happy memories can be revisited often (I don't think this link has the full clip, but you'll get the idea).

Billy's Balloon, by Don Hertzfeldt

It is possible that I am a bad person for finding this funny. You have been warned.

It is possible that I am a bad person for finding this funny. You have been warned.

Labels:

weblinks

Monday, June 05, 2006

Star Flight

This past Friday we gave our final presentations for my museum internship. It was basically a chance to show off our work to a handful of museum bigwigs -- it actually went pretty well, for the most part.

My group worked on two interactive computer exhibits. One exhibit (that I didn't work on very much) let people physically play with a virtual sound wave by moving an IR wand -- faster wand movement == smaller wavelength == higher frequency sound, and vice versa. The exhibit I worked primarily on (called 'StarFlight') allows people to fly through a 3D virtual reality model of our local universe with a video game controller.

For the most part it is very, very difficult to determine distances to astronomical objects -- in many ways, the problem of distance has been the central problem in astronomy for centuries now (and hopefully the topic of a future blog post). As a result, for many objects on the sky, we have very good 2D information, but only a rough estimate of the 3rd coordinate of radial distance. Inside a comparatively small radius about our sun, accurate distances to other stars in our galaxy can be determined through stellar parallax (which measures the apparent shift in positions of stars as the Earth goes around the Sun). The gold standard for this sort of measurement comes from the European Hipparcos satellite, which measured the parallaxes (and hence the distance to) nearly 120,000 of our closest stellar neighbors.

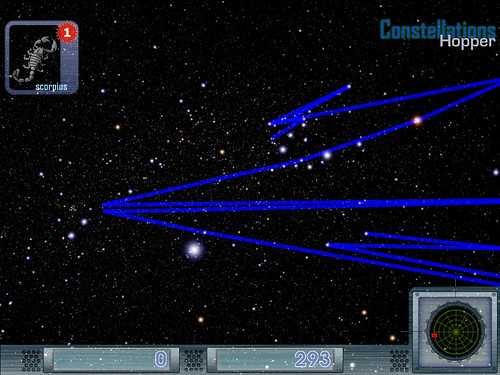

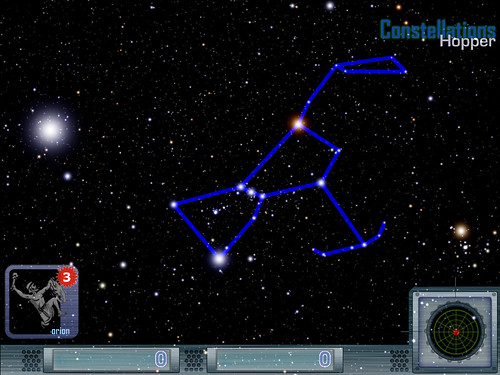

But more importantly, for our purposes, this dataset gives us a full 3D picture of our local corner of the Milky Way galaxy. Our exhibit lets the user "fly" through this cloud of stars just like a video game. Using this data, it's fun to consider what familiar constellations look like from different vantage points. For example, my sign is Scorpio, and this is what the constellation Scorpius looks like from Earth:

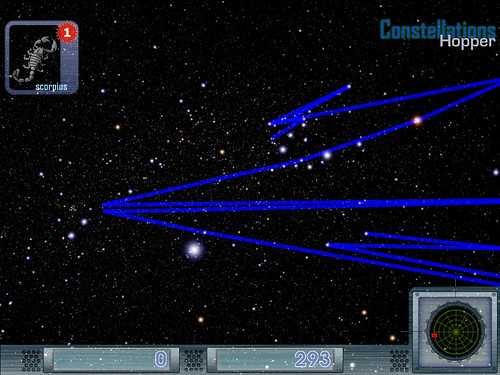

But when we fly off to one side and take a look it assumes this crazy zig-zag shape because some stars are really close to our sun and others are really far away. Our sun is represented by the tiny white circle on the far left that all the blue lines are "pointing to".

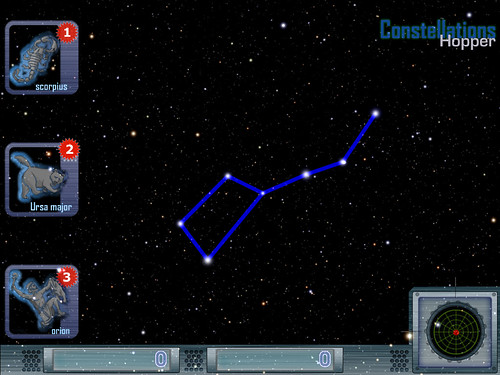

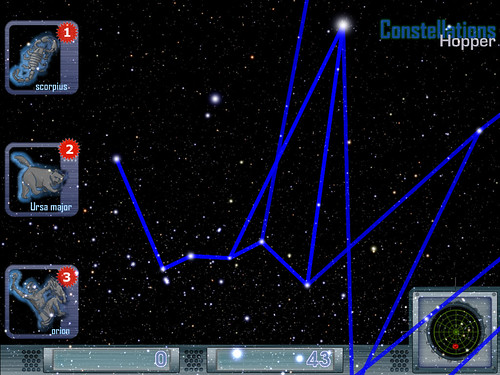

The basic implementation of the program is a mix between free form exploring of the stars with the video game controller, and a more guided tour of a few famous constellations, complete with narration explaining astronomical concepts and giving the mythological stories behind the shape. We also have an animated intro that puts everything in context by blasting off from downtown Chicago (Adler Planetarium actually) and launching us into the solar system, and finally out into the sea of nearby stars. The program can run on anything from a laptop screen (Mac, Win, Linux) to a GeoWall (a relatively inexpensive stereo 3D system that many museums use).

Implementing this exhibit took the combined efforts of many people, and it was aided infinitely by the existence of the very cool and super-useful electro application development environment. We will be distributing "StarFlight" on the web (link TBD) once we iron out a few more kinks, but since we based our program on a simpler implementation of the Hipparcos catalog (the 'total perspective vortex') that comes bundled with the electro download, you can try it yourself right away if you like. As a teaser here's an image of 'vortex' running on the 100-megapixel, 11x5 tiled display at the Electronics Visualization Lab at UIC. (Tangent: Can I just say EVL has some pretty impressive toys? In addition to the tiled display, we got to play with some of their varrier displays, which use various forms of eye- and head-tracking to create a personal stereoscopic 3D display without the use of annoying stereo glasses, which always give me a headache. They have it set up to do 3D video conferencing, which is a little freaky.)

So anyway, perhaps this exhibit will be effective in teaching a few basic astronomy ideas (stars are far away, but get brighter when you get close to them), and hopefully it will have a high 'cool factor' to hook visitors into playing with it. Participating in this project has given me nothing but respect for people who design human-computer interactions and museum exhibits. It is just not easy to design an object to do your communicating for you. With luck, 'StarFlight' will end up playing at SciTech Hands-On Museum in Aurora, IL (and maybe somewhere else too), and at any rate, was a lot of fun to make.

My group worked on two interactive computer exhibits. One exhibit (that I didn't work on very much) let people physically play with a virtual sound wave by moving an IR wand -- faster wand movement == smaller wavelength == higher frequency sound, and vice versa. The exhibit I worked primarily on (called 'StarFlight') allows people to fly through a 3D virtual reality model of our local universe with a video game controller.

For the most part it is very, very difficult to determine distances to astronomical objects -- in many ways, the problem of distance has been the central problem in astronomy for centuries now (and hopefully the topic of a future blog post). As a result, for many objects on the sky, we have very good 2D information, but only a rough estimate of the 3rd coordinate of radial distance. Inside a comparatively small radius about our sun, accurate distances to other stars in our galaxy can be determined through stellar parallax (which measures the apparent shift in positions of stars as the Earth goes around the Sun). The gold standard for this sort of measurement comes from the European Hipparcos satellite, which measured the parallaxes (and hence the distance to) nearly 120,000 of our closest stellar neighbors.

But more importantly, for our purposes, this dataset gives us a full 3D picture of our local corner of the Milky Way galaxy. Our exhibit lets the user "fly" through this cloud of stars just like a video game. Using this data, it's fun to consider what familiar constellations look like from different vantage points. For example, my sign is Scorpio, and this is what the constellation Scorpius looks like from Earth:

But when we fly off to one side and take a look it assumes this crazy zig-zag shape because some stars are really close to our sun and others are really far away. Our sun is represented by the tiny white circle on the far left that all the blue lines are "pointing to".

The basic implementation of the program is a mix between free form exploring of the stars with the video game controller, and a more guided tour of a few famous constellations, complete with narration explaining astronomical concepts and giving the mythological stories behind the shape. We also have an animated intro that puts everything in context by blasting off from downtown Chicago (Adler Planetarium actually) and launching us into the solar system, and finally out into the sea of nearby stars. The program can run on anything from a laptop screen (Mac, Win, Linux) to a GeoWall (a relatively inexpensive stereo 3D system that many museums use).

|  |

|  |

Implementing this exhibit took the combined efforts of many people, and it was aided infinitely by the existence of the very cool and super-useful electro application development environment. We will be distributing "StarFlight" on the web (link TBD) once we iron out a few more kinks, but since we based our program on a simpler implementation of the Hipparcos catalog (the 'total perspective vortex') that comes bundled with the electro download, you can try it yourself right away if you like. As a teaser here's an image of 'vortex' running on the 100-megapixel, 11x5 tiled display at the Electronics Visualization Lab at UIC. (Tangent: Can I just say EVL has some pretty impressive toys? In addition to the tiled display, we got to play with some of their varrier displays, which use various forms of eye- and head-tracking to create a personal stereoscopic 3D display without the use of annoying stereo glasses, which always give me a headache. They have it set up to do 3D video conferencing, which is a little freaky.)

So anyway, perhaps this exhibit will be effective in teaching a few basic astronomy ideas (stars are far away, but get brighter when you get close to them), and hopefully it will have a high 'cool factor' to hook visitors into playing with it. Participating in this project has given me nothing but respect for people who design human-computer interactions and museum exhibits. It is just not easy to design an object to do your communicating for you. With luck, 'StarFlight' will end up playing at SciTech Hands-On Museum in Aurora, IL (and maybe somewhere else too), and at any rate, was a lot of fun to make.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)